“In relation to [animals], all people are Nazis; for the animals, it is an eternal Treblinka.” –Isaac Bashevis Singer, The Letter Writer

I have something awful to confess; I am a murderer.

I killed my first victim back in the summer of 1987, when working at a prominent university’s basic science research center. I was a high school summer intern working in a lab. I had developed a strong interest in biology and the life sciences, and for the first time in my life I was flirting with the idea of considering a career in the health sciences. When I actually secured this intership, I was so grateful for the opportunity and there was nothing I wouldn’t do to make the most of it and excel at this coveted position.

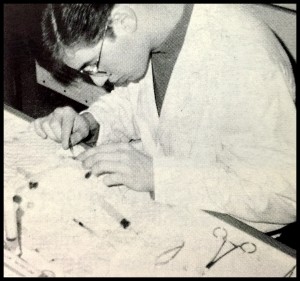

As a summer lab assistant, I learned how to handle rats, the subjects on whom we were testing the effects of a certain neuropeptide. I learned how to lift them by their tails with one hand, grab a hold of them from behind with the other hand and press down with my thumb and index finger to cross their arms to prevent them from biting me as I impaled their abdomens with large needles that delivered anesthetic to render them unconscious and hopefully, though certainly not always, insensate. Once they were anesthetized, I would incise their necks, bluntly dissecting down to their jugular arteries and veins. I eventually learned to carefully and skillfully catheterize these tiny vessels to gain access to administer medications and withdraw blood samples. I was learning how to do these procedures on living rats and I cannot count the number of individuals whose arteries and veins my unskilled 16 year old hands accidentally transected, causing them to bleed out and die on the table before ever getting to actually “do the experiment”. I always felt ashamed and upset when this happened. I wish I could say these feelings stemmed from the fact that I caused a feeling, thinking, sentient animal who did not consent to this procedure to die, often painfully and completely in vain, but that was not the reason. The truth is, I never stopped to consider my victims. I was only concerned with the fact that I could be perceived as “screwing up” and costing the lab money on these “lost” rats. I was only concerned about myself, my future in science and the review and recommendations I might get when I was done with my summer in the lab. Thanks to my innate manual dexterity, my learning curve was quicker than that of the other summer interns. I finally mastered these techniques and I moved on to more advanced vivisection. I became skilled at making midline incisions on the rats whose jugular arteries and veins I successfully catheterized, filleting open their abdomens and exposing all of their abdominal viscera to get to their urinary bladders. I would incise their bladders, catheterize them and collect urine samples. I worked diligently to impress my superiors of my skills in rat surgery and it paid off. I got the recommendations I had hoped to secure and this job was instrumental in planting the first seeds of self confidence in my mind that one day I might become a surgeon.

I remember the day that the head lab tech was doing a much awaited experiment on a puppy or, more precisely, on a puppy’s heart. I vividly remember the sweet little puppy who was brought into the lab in his plastic cage. Having not grown up with companion animals, I was wary of them though I always thought dogs and cats were cute. This puppy, like all puppies, was utterly adorable. He kept trying to lick the lab tech, kiss her and play with her. I must have cooed in my fawning over this cute little guy in his plastic cage because the lab director admonished me immediately. She told me that if I was going to stay and observe I had to be silent and not interact with the dog and if I couldn’t control myself, I should leave immediately. She confessed that she grew up with dogs and this was going to be an emotionally difficult experiment for her to do. Feeling like a puppy who had been scolded, I remained silent as I watched her gas this puppy into a quick and deep sleep. Then she abruptly cut into him, broke open his chest, frantically dissected blood vessels leading to and from his tiny and rapidly-beating heart. Then, in one quick and coordinated maneuver, she yanked out his heart from his tiny body and hooked it up to a machine that kept it beating. Immediately, the testing began and she was utterly consumed with the beating heart, carefully taking measurements, recording data and such. I became fixated on the puppy who was now dead and hauntingly lifeless, laying on the countertop beside the contraption that held in place his still beating heart suspended above. His chest cavity now overflowed with blood staining his soft tan fur. I must have been staring at the dead puppy with a look of sadness and horror because my unfiltered reaction agitated her. She stopped what she was doing for just a moment to collect his body and toss it into a trash bag. She tied a knot in the bag, handed it to me and said, “Here! Take this to the incinerator.” Banished from the lab for the duration of this experiment, I did as I was told and delivered his body for cremation, where I had brought so many of my own victims before.

It would be many years before I rescued my first companion animal from the Manhattan ACC, one of New York City’s many kill shelters. He was a black tan and white Chihuahua-mix called Blackie. One afternoon, about a year or so after adopting him, I awoke from a lazy afternoon nap with Blackie, though he remained sound asleep. I gently pressed my face up against his chest and was nearly startled by the sound of his rapidly-beating heart. I immediately flashed back to the puppy in the lab and felt completely overwhelmed with sadness. Now I was a doggy-daddy. I instantly revisited that suppressed memory from the lab and saw it from a totally different perspective. Dogs were now beings whom I considered individuals. Blackie was a member of my family who was deserving of my love, compassion and respect. My love for Blackie opened up my heart and the retroactive empathy for that murdered puppy began to flood in. I also began to feel subtle twinges of remorse for the innumerable rats I killed. However, still being quite speciesist in my thinking, it would be decades before I ever viewed their death and suffering in the same light as that of the puppy.

It’s taken me decades to get past the horrors that I inflicted “in the name of science” on countless non-human individuals. In the many years since choosing to live my life as a vegan, I’ve taken solace in the words of the late great American poet, Maya Angelou, “Do the best you can until you know better. Then when you know better, do better.” I have internalized this as a mantra for life. I apply it to help me reconcile my unthinking first 38 years of benefiting from the exploitation, torture and murder of tens of thousands of non-human animals. It has comforted me when I feel badly about the individuals whose corpses I mindlessly consumed as food; I now know better so I am doing better. But, as for the lab rats I murdered, this mantra offers me no solace. Perhaps it’s because, unlike the animal-derived foods I ate and clothes I wore, I was the one who did the actual killing. Or maybe it’s because I always doubted why we were studying animals to try and understand how things worked in humans. Even as a 16 year old working in a lab, there was a significant part of me that felt that research conducted on members of other species in the hopes of understanding the effects in humans is utterly unnecessary and fundamentally scientifically flawed, though I never dared say this back then. The hard truth about my personal time in the lab is that nothing scientifically beneficial came from any of the research we did. All done in the name of science and yet nothing was learned. Nothing was published and the scientific world benefitted nothing from our wasteful endeavors. There are countless ongoing research studies just like the ones in which I participated where nothing is gained, nothing is learned and everything is wasted, most significantly the lives of the non-willing participants. That is not to say that the end justifies the means and that an animal-model research study that is scientifically successful and beneficial excuses the torture and cruelty it imposes on it’s victims. Just like the cruel experiments the Nazi’s conducted on Jews during the holocaust, all data collected from non-consenting individuals will always be soaked in the blood of the victims and can never morally justified, even if it benefits individuals in the future.

When I think of the rats I murdered and the animals I’ve eaten, it feels different. This has bothered me for quite some time because I have deemed these actions as morally comparable. In the process of exploring my feelings and revisiting this disturbing part of my past, I’ve come to accept that it should feel different. I have gotten away with murder. I now realize that it’s critical for those of us who have acted in this way and then woken up to the realities of animal sentience and abuse, not to shy away from the horrors of our past. We must make people aware that vivisection is not just a horror for the animals; it affects the perpetrators of these experiments as well. Just like those who do the brutal work on our behalf in slaughterhouses, murdering animals for their flesh and secretions, vivisection isn’t just a horror for the animal victims. It deeply negtively impacts the lives and spirits of the people who are charged to do this dirty work on our behalf as well. As I continue to fight the good fight to help bring about animal liberation, including an end to vivisection and animal experimentation, I often wonder if the haunting feelings of remorse and guilt will ever abate or disappear. Part of me hopes they never will, because they are equally potent in their capacity to haunt me as well as to motivate me to fight harder to finally bring an end to the still-ongoing horrors of vivisection and animal murder, of which I am entirely guilty.